History of CNC Machining Part 2: The Evolution from NC to CNC

At Bantam Tools, we build desktop CNC (computer-numerically controlled) machines with professional reliability and precision to support world changers and skill builders. We set out on a journey to explore the history of CNC. The comprehensive story hasn’t been told, and we feel it should be, so we invested the time to research it. What we found was an intriguing story of the human quest for increased efficiency and precision through machinery.

In this three-part series, we share what we learned. While we did dig deep, if we missed an important person or device, please let us know in the comments. Be sure to check out Part 1, The People, Stories, and Inventions That Made Today’s Tech Possible, and Part 3, From the Factory Floor to the Desktop.

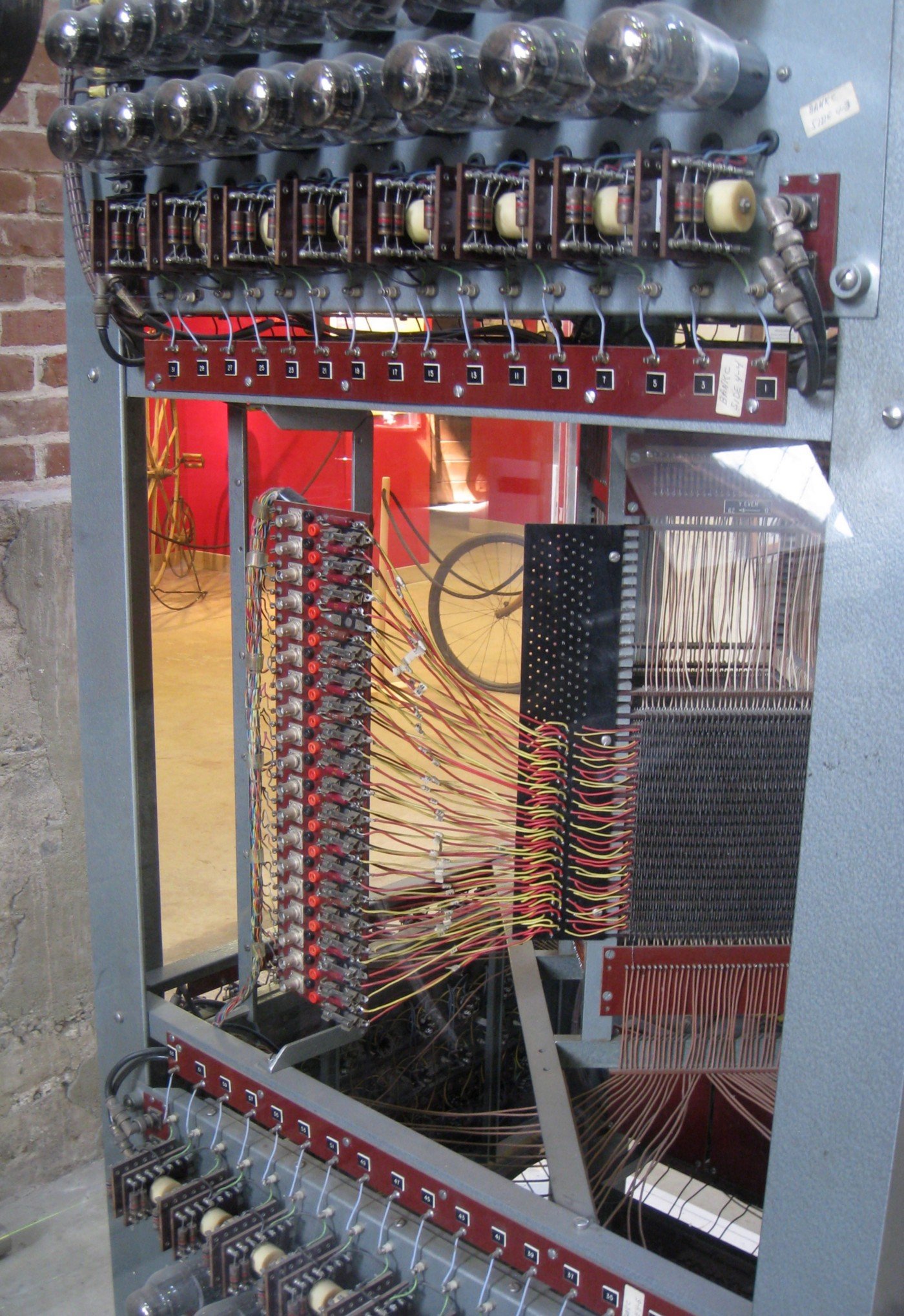

Project Whirlwind core memory, circa 1951. [Image Source]

Up until the 1950s, numerically controlled machines ran on data from punched cards largely made using a painstaking manual process. The turning point in the evolution to CNC is when the cards were replaced with computer control, which maps directly to the development of computers, as well as computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) programs. Machining became one of the first applications of computing.

Although Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine, developed in the mid-1800s, is credited as being the first computer in the modern sense, Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) real-time computer Whirlwind I (also born out of the Servomechanisms Lab) was one of the first to calculate in parallel and use a magnetic core memory (pictured below). The team was able to use the machine to code computer-controlled production of punched tape. The original Whirlwind used about 5,000 vacuum tubes and weighed roughly 20,000 lbs.

John Parsons, on why it took so long between licensing the NC patent and the widespread use of NC:

“The slow progress of computer development was part of the problem. In addition, the people who were trying to sell the idea didn’t really know manufacturing — they were computer people. The NC concept was so strange to manufacturers, and so slow to catch on, that the US Army itself finally had to build 120 NC machines and lease them to various manufacturers to begin popularizing its use.”

Timeline of the Evolution from NC to CNC

Mid-1950s: G-code, the most widely used NC programming language is born out of the MIT Servomechanisms Lab. G-code is used to tell computerized machine tools how to make something. Instructions are sent to the a machine controller, which then tell the motors how fast to move and what path to follow.

1956: The Air Force proposes creation of a general programming language for numerical control. A new MIT research division, led by Doug Ross and named the Computer Applications Group, begins work on the proposal, developing what would become known as the programming language Automatically Programmed Tool (APT).

1957: The Aircraft Industries Association and a division of the Air Force collaborate with MIT to standardize the work with APT and create the first official CNC machine. Created before graphical interfaces and FORTRAN were invented, APT used text alone to convey geometry and toolpaths to a numerically controlled (NC) machine. (Later versions were written in FORTRAN, and APT was eventually released in the public domain. Check out AptStepMaker for a modern rendition.)

1957: While working at General Electric, American computer scientist Patrick J. Hanratty develops and releases an early commercial numerical control programming language named Pronto, laying the foundation for future CAD programs and earning him the informal title “Father of CAD/CAM.”

“On March 11, 1958, a new era in manufacturing production was born. For the first time in the history of manufacturing, a number of large production machines, electronically controlled, were functioning simultaneously as an integrated production line. Virtually unattended, these machines were drilling, boring, milling, and passing unrelated parts from machine to machine.”

1959: The MIT team holds a press conference to showcase their new CNC machine development. Famously, a CNC-milled aluminum ashtray is handed out as part of the press kit.

1959: The Air Force signs a one-year contract with MIT’s Electronic Systems Laboratory for development of the “Computer-Aided Design Project.” The resulting system, Automated Engineering Design (AED), was released to the public domain in 1965.

1959: General Motors (GM) starts work on what would become known as Design Augmented by Computer (DAC-1), one of the earliest graphical CAD systems. In the second year, they brought in IBM as a collaborator. Drawings could be scanned into the system, which digitized them, and modifications could be made. Additional software could then convert the lines into a 3D shape and output into APT for sending to milling machines. DAC-1 was released to production in 1963 and publicly unveiled in 1964.

1962: The first commercial graphical CAD system, Electronic Drafting Machine (EDM), developed at U.S. defense contractor Itek, becomes available. Purchased by mainframe and supercomputer firm Control Data Corporation, it was renamed Digigraphics. It was initially used by the likes of Lockheed Corporation to build production parts for the C-5 Galaxy military transport aircraft, demonstrating the first example of an end-to-end CAD/CNC production system.

Time Magazine wrote about EDM in March of 1962, noting:

“The operator’s designs pass through the console into an inexpensive computer, which solves the problems and stores the answers in its memory banks in both digitized form and on microfilm. By simply pressing buttons and sketching with the light pen, the engineer may enter into a running dialogue with an EDM, recall any of his earlier drawings to the screen in a millisecond and alter its lines and curves at will.” [Source]

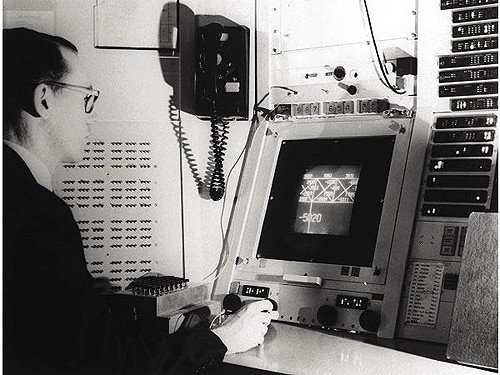

1963: Ivan Sutherland, a PhD candidate at MIT, submits his thesis titled “Sketchpad: A Man-Machine Graphical Communication System,” describing the first graphical user interface, which ran on MIT Lincoln Labs’ TX-2 computer (a transistorized version of Whirlwind), one of the world’s biggest and most powerful machines at the time, with 306 kilobytes of core memory.

TX-2 had an oscilloscope display screen, programmable buttons for entering commands, a light pen for input, and a pen plotter for output, enabling Sketchpad to be interactive, as opposed to previous programs, which were batch-oriented. Sketchpad eliminated typed statements in favor of line drawings, particularly helpful when communicating things like the shape of a mechanical part or the connections of an electrical circuit.

Ivan Sutherland working on TX-2. [Image Source]

Diagram of the light pen Sutherland used on TX-2 with Sketchpad. [Image Source]

Sketchpad in Action

“Mechanical and electrical designers needed a tool to speed up their oft-times arduous and time-consuming work. To fulfill this need, Ivan E. Sutherland of the MIT electrical engineering department created a system for making a digital computer an active partner of the designer. “

CNC Machines Gain Traction and Popularity

During the mid-60s, the advent of affordable minicomputers was a game changer to the industry. These powerful machines took up much less space than the room-sized mainframes used to date, thanks to the new transistor and core memory technologies.

Minicomputers, also known at the time as midrange computers, naturally also came with a more affordable price tag, freeing them up from the previous confines of a corporation or the military and putting the potential of precision and reliable repeatability in the hands of smaller companies and businesses.

In contrast, microcomputers were 8-bit single-user, simple machines that run simple operating systems like MS-DOS, while superminis were 16-bit or 32-bit. Pioneering companies include DEC, Data General, and Hewlett-Packard (HP) (who now refers to its former minicomputers, like the HP3000, as “servers”).

During the early 1970s, slow economic growth and rising employment costs made CNC machining seem like a great, cost-effective solution, and demand for lower-cost NC system machines increased. While U.S. researchers were focused on software and high-end industries like aerospace, Germany (joined by Japan in the 80s) surpassed the U.S. in machine sales by focusing on the low-cost markets. There were, however, an array of American CAD firms and vendors at this point, including UGS Corp., Computervision, Applicon, and IBM.

In the 1980s, as the cost of microprocessor-based hardware dropped and local area network (LAN, a computer network that interconnects to others) systems emerged, so did the cost and accessibility of CNC machines. By the second half of the 80s, minicomputers and large computer terminals were replaced by networked workstations, file servers, and personal computers (PCs), untethering CNC machines from the universities and companies that traditionally housed them (since they were the only ones who could afford the expensive computers that accompanied them).

In 1989, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, an agency of the US Government’s Department of Commerce, created the Enhanced Machine Controller project (EMC2, later renamed LinuxCNC), an open-source GNU/Linux software system to control CNC machines using general purpose computers. LinuxCNC paved the way for a future of personal CNC machines, which continued to be a pioneer application for computing.

Thank you for joining us on this journey through CNC history. At Bantam Tools, we make desktop CNC machines with reliability and precision at an affordable price. Bantam Tools looks forward to further exploring the frontier of creative and empowering machines. Follow our journey on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and be sure to subscribe to the Bantam Tools mailing list to receive more content like this.

Continue on to:

Part 1, The People, Stories, and Inventions That Made Today’s Tech Possible

Part 3, From the Factory Floor to the Desktop

Researched and written by staff writer Goli Mohammadi for Bantam Tools.